Of the 150 psalms in the book known in Hebrew as “Tehillim,” the 23rd may be the best known: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.”

The late rabbi Adin Steinsaltz explained that the verse compares the speaker to a lamb, and that God the shepherd “will lead him on a secure path and provide him with a dwelling in a good and happy place.”

But what if there is no good and happy place? What if a person who recited Tehillim all her life found herself in the hell of Auschwitz or Dachau, her prayers unanswered, her paths blocked by SS guards? Did she die still believing? Can the survivors and the generations of Jews who came after them still recite the psalms and mean it?

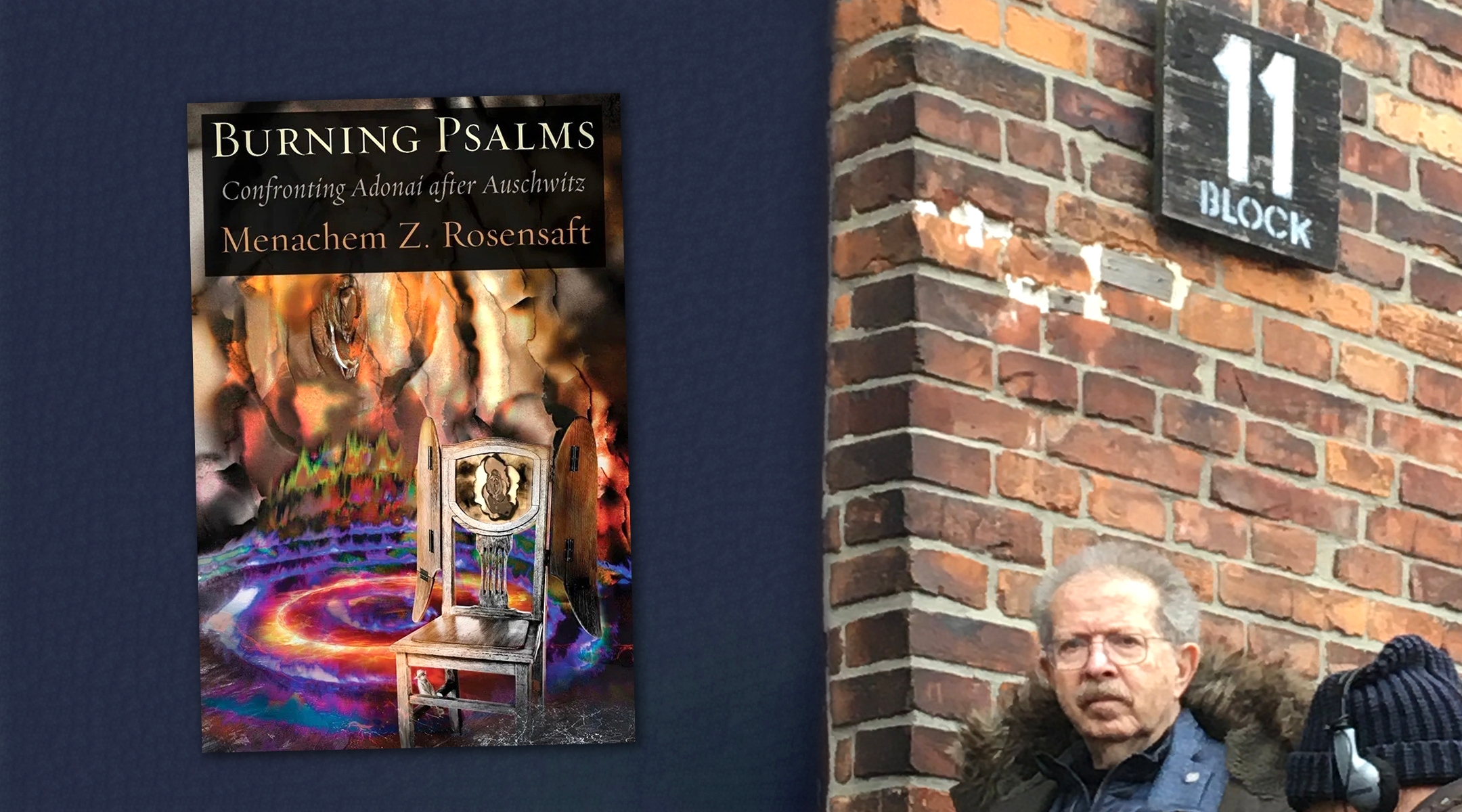

Those are some of the questions Menachem Rosensaft asks in a new book of poetry, “Burning Psalms: Confronting Adonai After Auschwitz.” An attorney and Jewish activist who was born in the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp to two Holocaust survivors, Rosensaft has written a series of “response” poems corresponding to each of the psalms, holding God accountable for remaining silent during the slaughter. His version of Psalm 23 begins, “A psalm to the emptiness/ no shepherd / only foes….”

“If we are serious about our relationship with God,” Rosensaft, who lives on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, said in an interview this month, “then we have to express our grievances and not just extol the miracles of thousands of years ago without even acknowledging that there was no divine presence that came to any assistance” for the 6 million Jewish victims of Hitler.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day is Monday, Jan. 27, when the world pauses to consider the many lessons of the Holocaust: “Never again.” A pledge to stop genocides anywhere. A commitment to honor and assist the dwindling number of survivors, and to fight the antisemitism that persists 80 years after the liberation of Auschwitz.

Rosensaft, the founding chairman of the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, has taken part in numerous such ceremonies, and endorses each of those messages. But “Burning Psalms” is in part a response to movies, speeches and books that emphasize the stories of resilience and heroism on the part of survivors and rescuers, and look away from the bleakness of the genocide and the helplessness of the victims.

Melissa Leo is among the actors who read and dramatize poetry about the Holocaust in the 2024 documentary “After: Poetry Destroys Silence.” (Lumen Productions)

Poetic responses to the Holocaust are as diverse as the people who write them, as demonstrated in the 2024 documentary, “After: Poetry Destroys Silence.” (The film will be screened at the Marlene Meyerson JCC Manhattan on Tuesday, Jan. 28 at 7:00 p.m., with a talkback featuring producer and poet Janet R. Kirchheimer, poet and actor Géza Röhrig and poet Edward Hirsch, moderated by writer and psychologist Eva Fogelman.)

The poets whose works are read and dramatized in the film variously try to understand the relatives they have lost, the world’s ability to go on after genocide, and the overwhelming history that haunts them. Hirsch, like Rosensaft, explores God’s absence during the Holocaust. In the film, Hirsch reads his poem “My First Theology Lesson,” in which his grandfather’s friend declares that God left “ourselves alone in a divine wilderness.”

Despite the darkness of the film, Kirchheimer — who lives in Riverdale, New York and in the film reads a poem about her refugee parents — nevertheless sees hope in the ways poets use art to remember the Holocaust. “This film is really ultimately about hope,” she told me in an interview. “Remembrance is, ultimately, hopeful, because this is the world we’re living in, and people still go on.”

Rosensaft understands how hope and despair collided in the camps. His father, Josef, a native of Będzin in southern Poland, somehow survived Block 11, the notorious “death block” at Auschwitz, while his wife and her daughter were taken to the gas chambers upon their arrival at Birkenau. In September 1944, Josef led Yom Kippur prayers for his fellow prisoners in the death block.

At the displaced persons camp set up at Bergen‐Belsen after its liberation in 1945, Josef met Rosensaft’s mother Hadassah, whose parents, husband and 5-year-old son, Benjamin, were killed in the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau. A physician, she survived as a member of a medical detail under the sadistic SS doctor Josef Mengele, and managed to provide compassionate and even life-saving care to women and children.

Menachem was born in Bergen-Belsen on May 1, 1948. The family remained in the DP camp until it was closed in 1950, and eventually settled in New York in 1958. Rosensaft served as general counsel of the World Jewish Congress and teaches law at Columbia and Cornell.

Rosensaft’s version of Psalms is animated by his father’s sustained if qualified belief in God despite the horrors he and Rosensaft’s mother endured.

Menachem Rosensaft leads a tour of the Auschwitz II-Birkenau complex for members of the World Jewish Congress, January 2020. (New York Jewish Week)

“Somebody once asked him, ‘Do you still believe in God after the Holocaust?’” Rosensaft recalled. “So my father said, ‘Look, I’m not holding God responsible for the Holocaust. But on the other hand, I’m not giving him any medals for it either.’

“And I think that’s sort of the way of trying to navigate it.”

Ultimately, by confronting God through liturgy, Rosensaft hopes to raise awareness of the Shoah not just in museums and memorials, but in synagogues. He thinks the prayers written in memory of the Holocaust — for Yom Kippur, for Yom Hashoah and other occasions — do not adequately address the dilemmas of belief following the genocide.

And while Rosensaft’s responses to Psalms criticize the God whose face was hidden when the poet’s own brother died, he remains what he calls “a Jew who believes — or wants to believe — in God.” Like a number of post-Holocaust theologians — including Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, Emil Fackenheim and Abraham Joshua Heschel — he believes in a God who withdrew at a pivotal moment, allowing humans to fill the void with both evil and goodness.

“There was a divine presence within every Jew who helped another Jew in a barrack, who comforted, who shared some bread, who told a joke, who cradled someone, who comforted a child going into a gas chamber,” said Rosensaft. “There was the Divine Presence within every non-Jew who helped risk their life to help another Jew.

“God was absent from the perpetrators, from those who looked away.”

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.