“Blacklisted: An American Story,” a new exhibit at New York Historical, explores a dark chapter of the 1940s and ’50s, when fears of communism led to government investigations of Hollywood and industry-imposed blacklists that silenced many entertainment professionals.

Using a rich display of artifacts —such as telegrams, costumes, movie posters and archival video — the exhibit explores the impact the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had on Hollywood actors, writers and directors as it sought to root out alleged communist propaganda in the film business.

It’s undoubtedly an American story, as the exhibit’s tagline suggests. But it is also a deeply Jewish one.

“Even the choice to target the film industry was motivated in part by recognition of visible and successful Jewish Americans,” Anne Lessy, curator of the exhibit at New York Historical, told the New York Jewish Week, pointing to the abundance of Jews in Hollywood.

Take, for example, the “Hollywood 10” — 10 film directors and screenwriters who, in 1947, were cited for contempt of Congress by refusing to answer HUAC’s questions and were subsequently blacklisted from the industry. Six of the Hollywood 10 were Jewish: screenwriter Alvah Bessie; screenwriter and director Herbert Biberman; screenwriter Lester Cole; playwright and screenwriter John Howard Lawson; playwright and screenwriter Albert Maltz, and screenwriter and novelist Samuel Ornitz.

“Certainly members of the Hollywood Ten also felt that they were being targeted for being Jewish,” Lessy said.

The exhibit originated in 2018 at the Jewish Museum Milwaukee. As it happens, the nearby University of Wisconsin – Madison is home to one of the largest archives of Hollywood blacklist materials, according to Ellie Gettinger, the former director of education at the museum, who curated the exhibit. (Joseph McCarthy, the Republican senator who is most closely associated with what is known as “the Second Red Scare,” also hailed from the state, though he was not involved in the HUAC hearings.)

“There were certainly people who were motivated by antisemitism,” Gettinger said, adding that she hesitates to label the Hollywood Blacklist as an antisemitic event.

“For Hollywood, I think, this was a way of getting their labor issues under control,” she said. “You get the people who are more active labor activists out of the industry, then it’s going to be a lot easier to get contracts and things through.”

Certainly, not everyone involved was Jewish, and some of the people who carried out the Blacklist — like studio executives — were Jews.

“They also might have felt extra pressure because of their Judaism,” Gettinger added.

Since its initial run in Milwaukee, the exhibit traveled to the Jewish Museum in Maryland and to the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles in 2023, where it also included new materials related to the film industry. Here in New York, the exhibit has been further expanded to include Broadway and the theater industry.

“Whether you’re Jewish or not, I think that there’s a definite Jewish aspect to the story that we wanted to be able to portray,” Ettinger said.

Keep scrolling to learn about six Jewish highlights in the exhibit, which is on view through Oct. 19.

1. A pamphlet about deportation by Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman

An original copy of a pamphlet written by anarchist political theorists Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

About 20 years before HUAC was formed, Lithuanian Jewish immigrants Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman — well-known anarchists and political thought leaders — were deported from the United States for their revolutionary views.

In 1919, the pair published a pamphlet, “Deportation: Its Meanings and Menace; Last Message to the American People,” a manifesto criticizing the American treatment of Russian-Americans and immigrants who face deportation. This manifesto was written while the pair were held at Ellis Island’s Deportation Station during the first Red Scare, which came after the Bolshevik Revolution succeeded in overthrowing the Russian empire.

Hundreds of immigrant activists were deported around this time, including Berkman and Goldman. Their story parallels that of those blacklisted by Hollywood: they were vocal political dissidents making their way on the scene on the heels of a world war — in this case, World War I — and they were Jewish.

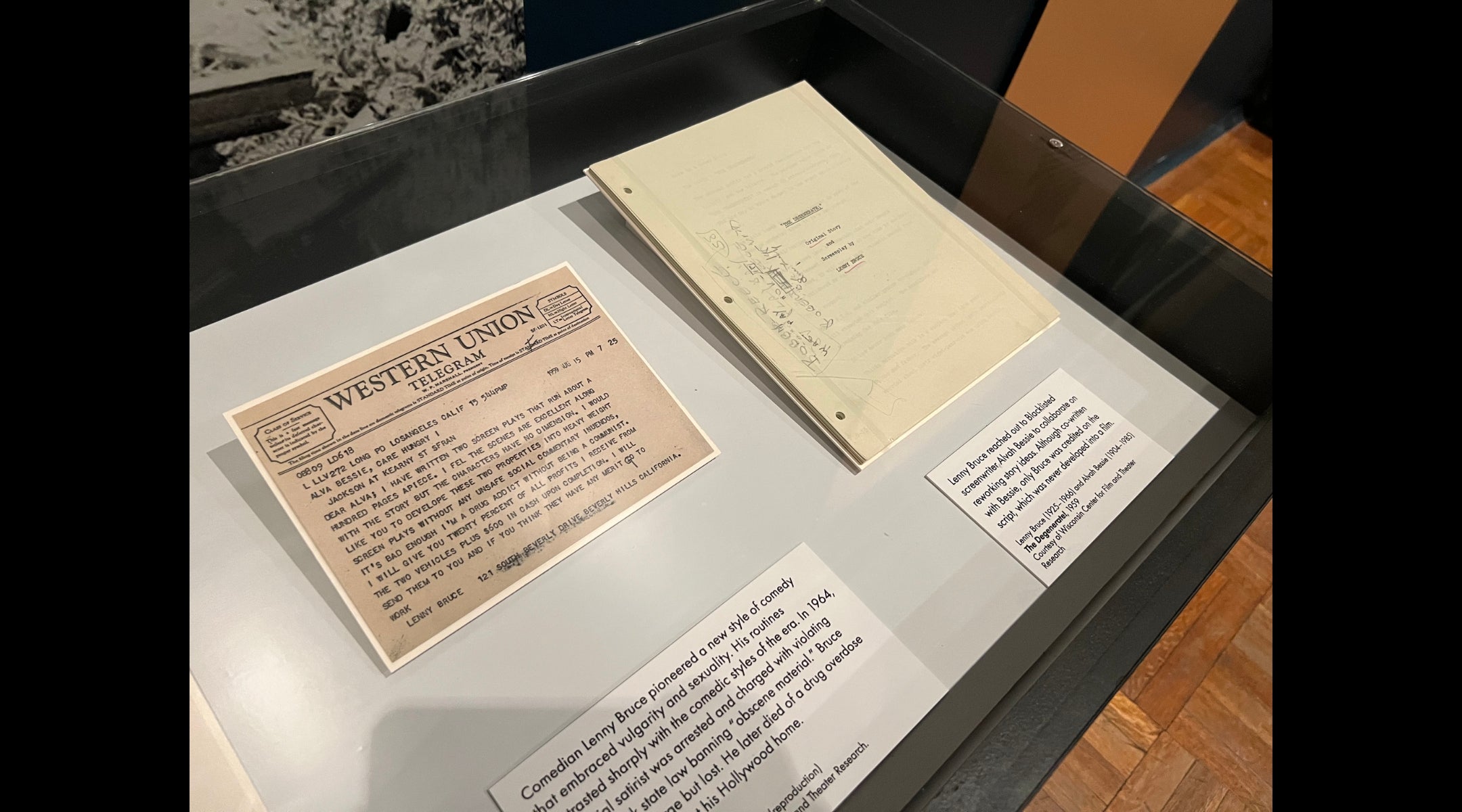

2. An unproduced screenplay by Lenny Bruce and Alvah Bessie

Artifacts from comedian Lenny Bruce related to his unpublished works with blacklisted screenwriter Alvah Bessie. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, comedian and free speech advocate Lenny Bruce — born Leonard Schneider in Mineola, New York — spearheaded a new kind of standup comedy blended biting social critique with foul language and overt sexuality.

Bruce was frequently arrested for his use of obscene language during his standup routines as a result. Though he wasn’t on the HUAC blacklist, the Jewish comedian was barred from television and from numerous nightclubs across the country.

In 1959, he reached out to blacklisted Jewish screenwriter Alvah Bessie, one of the Hollywood Ten, to collaborate on a screenplay he had written. “The Degenerate” became one of three screenplays the pair co-wrote that were never developed.

Bessie, a card-carrying member of the Communist Party who refused to testify in Congress, served his prison term for contempt of Congress in Texas for 10 months. He left the party in 1954, and when the blacklist period ended, was able to find work again writing several more screenplays. He died of natural causes in 1985. Bruce died of an overdose in 1966 at age 40 while out on bail for an obscenity trial.

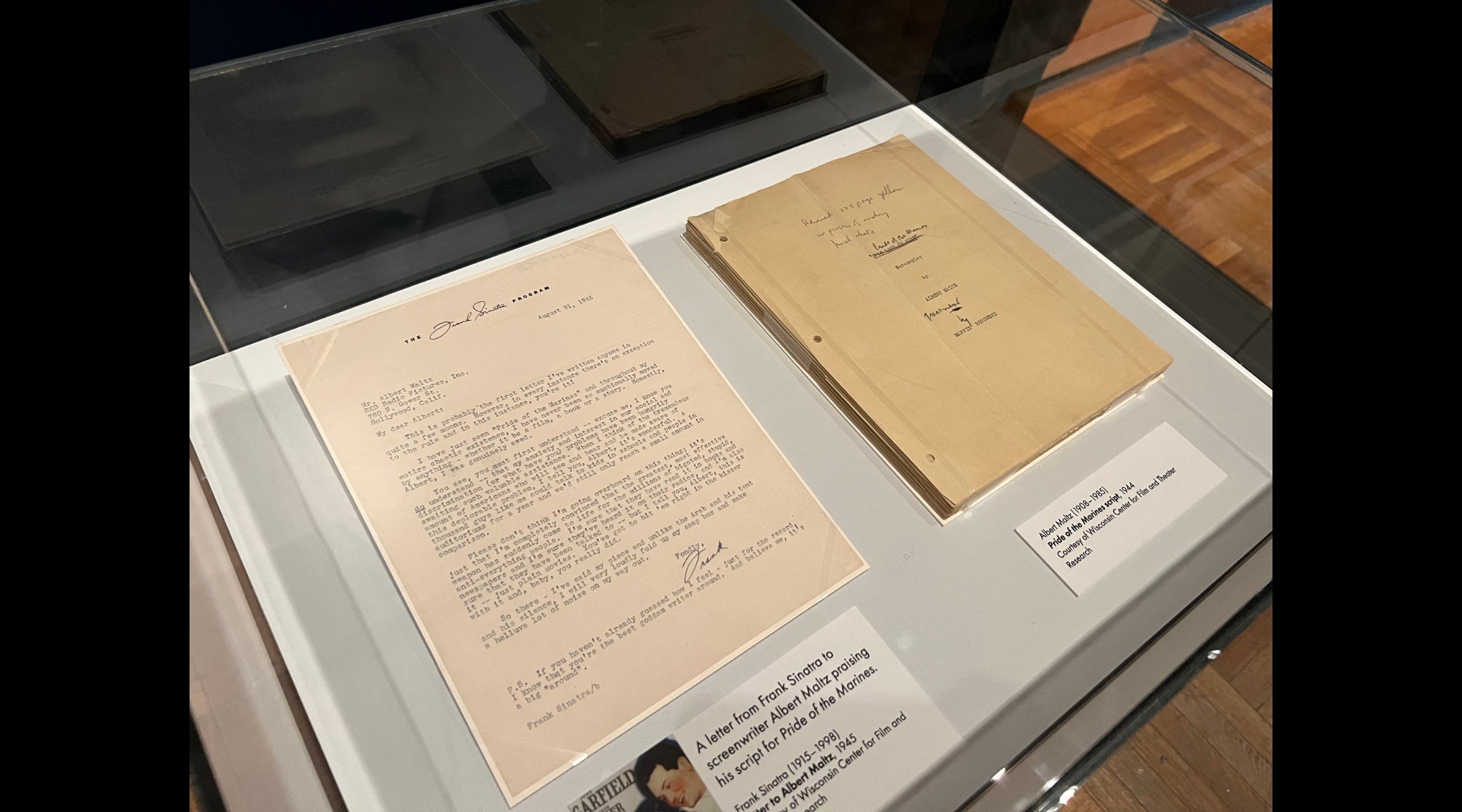

3. Letter from Frank Sinatra to blacklisted playwright and screenwriter Albert Maltz

A telegram from Frank Sinatra to screenwriter Albert Maltz. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

In this letter dated 1945, actor and crooner Frank Sinatra — a Democrat who championed liberal causes throughout his life — praises screenwriter Albert Maltz for the script for “Pride of the Marines,” for how it handled “social and discrimination (or what have you) problems.”

The film, which was released in 1945, is based on the true story of U.S. Marine Al Schmid, who was blinded by a hand grenade during the Battle of Guadalcanal in the Pacific during World War II. Starring John Garfield — one of the Jewish Hollywood insiders who was called to testify before HUAC — the film explores Schmidt’s long journey of recovery. (Garfield died of a heart attack in 1952 at the age of 39, which some attributed to the extra stress of the blacklist period.)

“… When I think of the tremendous amount of Americans who will see and hear and be made aware of this deplorable problem, I tell you, Albert, it’s wonderful,” Sinatra wrote. “A thousand guys like me could talk to kids in schools and people in auditoriums for a year and we’d still only reach a small amount in comparison.

Please don’t think I’m going overboard on this thing; it’s just that I’m completely convinced that the greatest, most effective weapon has suddenly come to life for the millions of bigoted, stupid, anti-everything people. I’m sure that they have read it in books and newspapers and I’m sure that they’ve heard it on their radios, and I’m also sure that they have been talked to – but I tell you, Albert, this is it – just plain movies. You’ve got to hit ‘em right in the kisser with it and, baby, you really did.”

Maltz, who became a member of the Hollywood 10, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for this script. Maltz continued working during and after the blacklist uncredited, or sometimes under the pseudonym John B. Sherry.

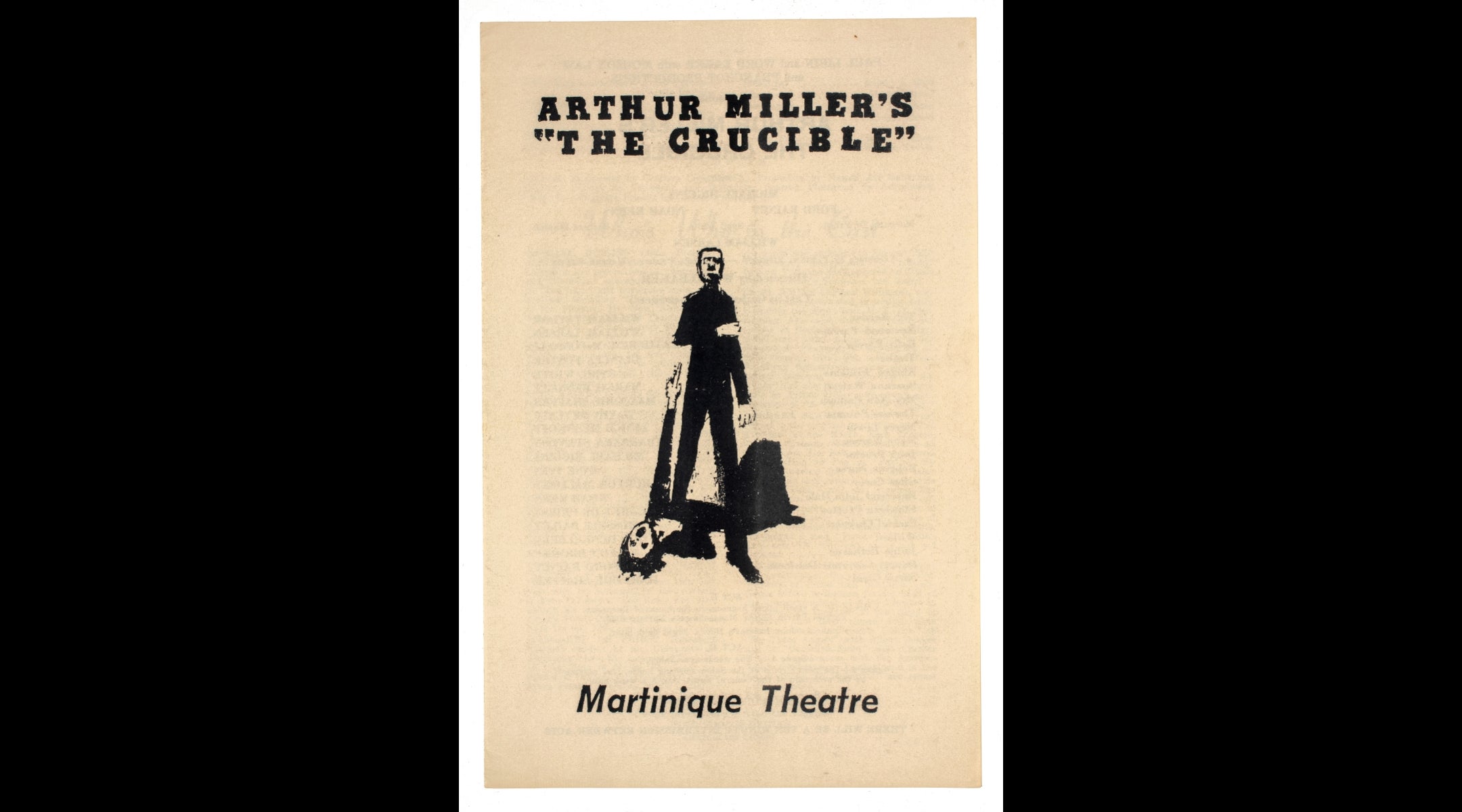

4. Playbill from a 1958 staging of Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible”

Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” was staged at the Martinique Theater in 1958. (Courtesy The New York Historical)

When it first hit Broadway in 1953, Jewish playwright Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” swept the Tony Awards, winning the prize for Best Play that year. Set during the Salem witch trials, “The Crucible” is an allegory for the Red Scare, the HUAC hearings and ideological persecution in general.

This playbill is from a revival of the show during a 1958 run put on in the converted ballroom of the Martinique Hotel in Midtown.

Miller was questioned by Congress in 1956, accompanied by his wife, Marilyn Monroe. He detailed his own political involvements — including attending a few meetings held by writers affiliated with the Communist party — but refused to name names. Miller was found in contempt of Congress but did not serve time; the conviction was overturned in 1958.

Miller was not officially blacklisted from Hollywood, namely because his work was not in film. But his passport was denied by the State Department.

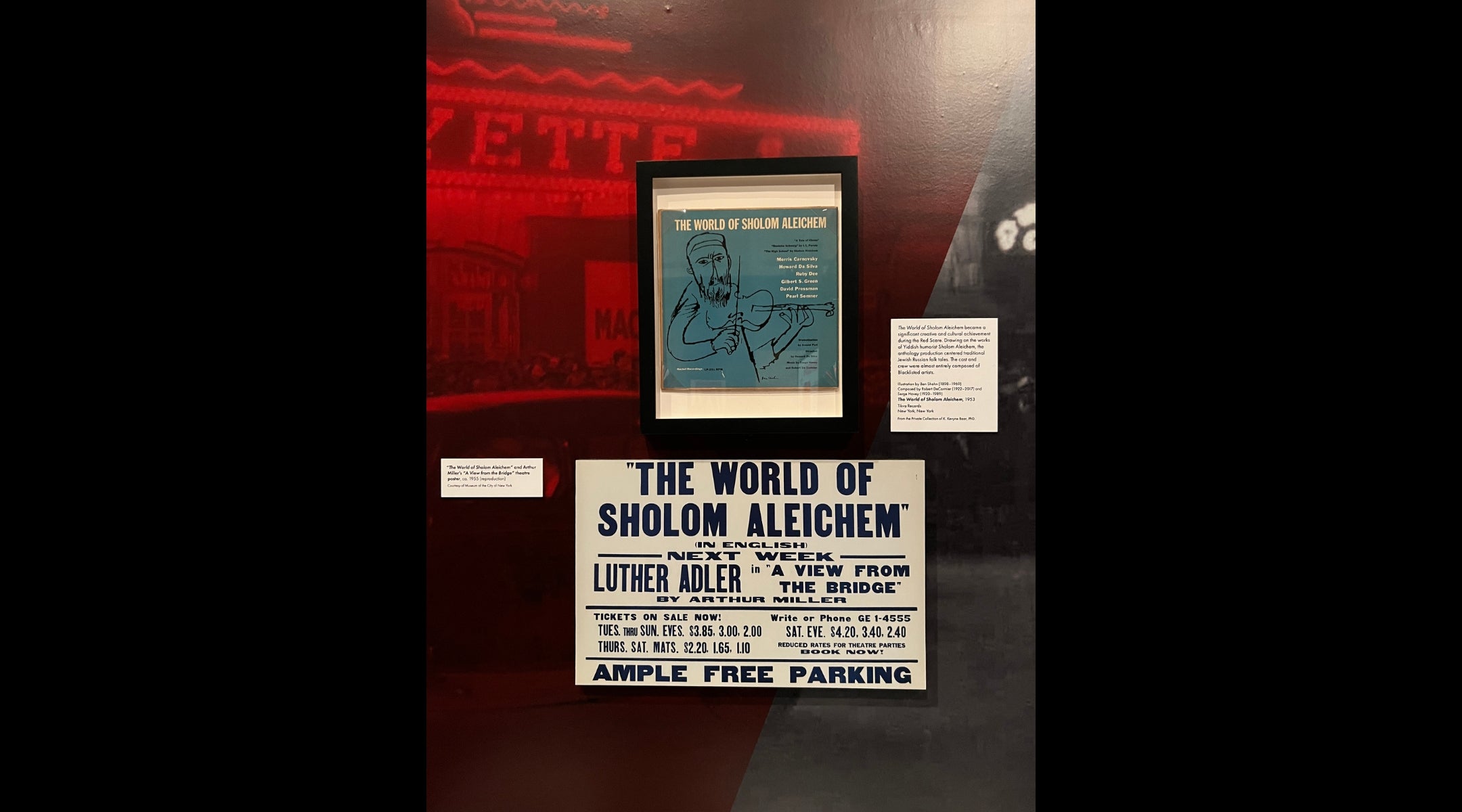

5. “The World of Sholom Aleichem” record and program

A record sleeve for ‘The World of Sholom Aleichem,’ whose cast and crew was primarily composed of blacklisted individuals. (Jackie Hajdenberg)

This three-story anthology play, based on the works of Yiddish literature giants Sholom Aleichem and I.L. Peretz, became an off-Broadway hit in 1953. Written by Maurice Samuel and adapted for the stage by Arnold Perl, “The World of Sholom Aleichem” featured a cast made up almost entirely of blacklisted Jewish actors, including Jack Gilford and his wife, Madeline Lee. It was staged at Theater 1199, a performing arts initiative of Healthcare Union 1199, which was founded in 1932 by (primarily Jewish) pharmacy workers, and expanded in later years to sponsor and stage political pieces.

In its first run, “The World of Sholom Aleichem” featured three stories: “A Tale of Chelm,” by I.L. Peretz; “Bontche Schweig,” by I.L. Peretz; and “The High School,” by Sholem Aleichem. It ran for two years, and preceded the adaptation of Sholom Aleichem’s story “Tevye the Dairyman,” which became “Fiddler on the Roof,” the 1964 musical starring blacklisted actor Zero Mostel.

6. Lauren Bacall’s costume from “How to Marry a Millionaire”

Lauren Bacall’s costume from 1953’s “How to Marry a Millionaire.” (Costume and photo courtesy of The Collection of Motion Picture Costume Design, Larry McQueen. Photo by CMPCD)

Born Betty Joan Perske to Jewish parents in the Bronx, Lauren Bacall is considered one of the greatest Hollywood actresses of all time, catapulting to stardom with the 1944 “To Have and Have Not,” in which she starred opposite her future husband, Humphrey Bogart.

Bacall was also a founding member of the Committee for the First Amendment, a group organized to defend artists and creatives in the film industry from HUAC. Bacall eventually dissociated herself from the Hollywood Ten, after a much-publicized Hollywood delegation including Danny Kaye, John Huston and Bogart, flew to Washington as part of the committee in the fall of 1947 to protest the HUAC hearings.

In May, 1948, she appeared in a photograph alongside Bogart in an op-ed he wrote for Photoplay magazine headlined “I’m No Communist,” in which he claimed he was “as much in favor of communism as J. Edgar Hoover,” and that he joined the committee to protect free speech and the Bill of Rights — not to protect communists.

On display at the exhibit is the two-piece suit that Bacall wore as Schatze Page in the film “How to Marry a Millionaire” in 1953 — the height of the Red Scare.

Though many committee members lost job opportunities over the next several decades due to their involvement defending the Hollywood Ten, Bacall continued working until her death in 2014.

“Blacklisted: An American Story” is on view at the New York Historical (170 Central Park West) through Oct. 19.

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.