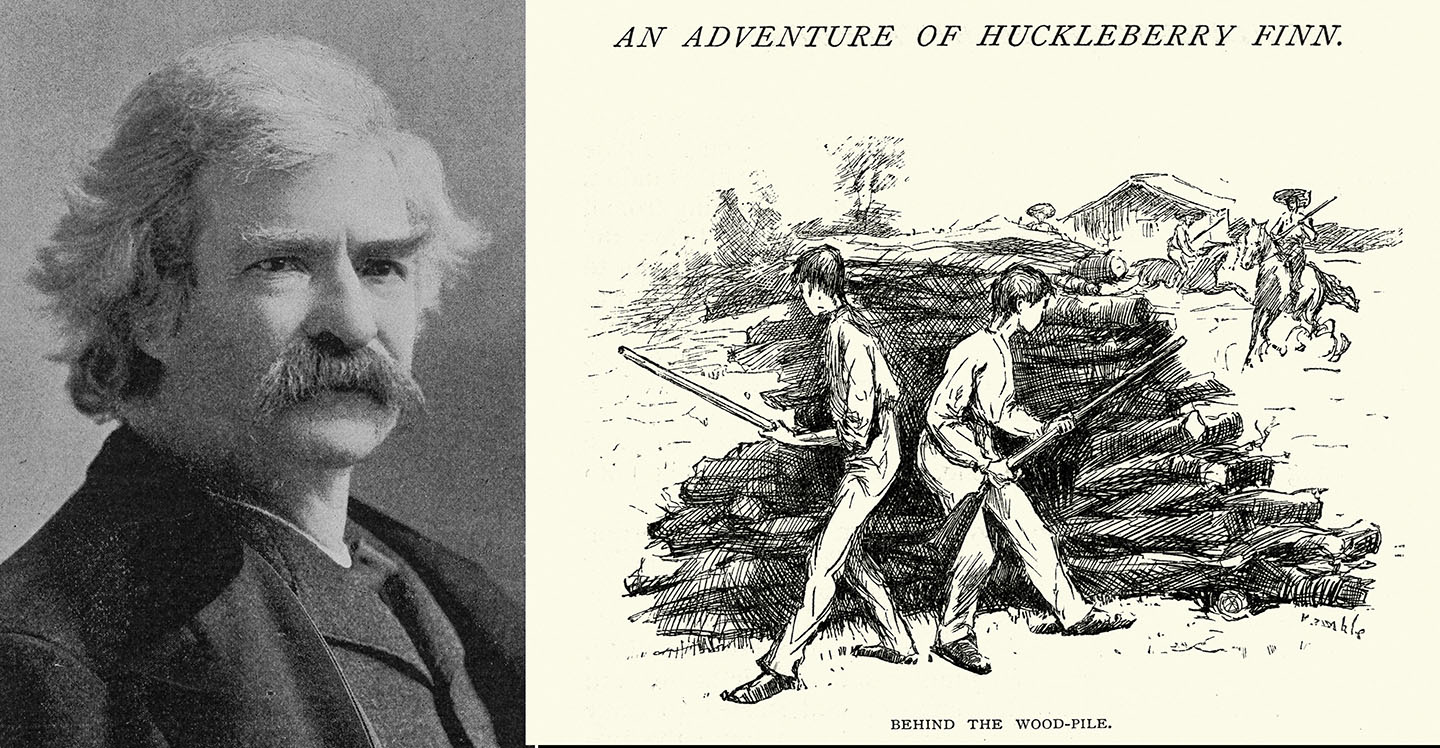

Mark Twain’s novel “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” published in 1884, is sometimes banned because of its constant use of the horrific term “nigger,” yet it is the least racist book imaginable. In fact, it is anti-racist.

It is the story of a rebellious young boy in the pre-Civil War South who runs away from a sad family life. He was raised in a racist society and assumes its prejudices as if they are natural and normal. The use of the racist word for Blacks is the clear signal that Huck, in spite of his rebelliousness, is very much the product of his society.

He meets a Black man, a runaway slave named Jim, during his travels and the two runaways end up forming a bond. For the first time in his young life, Huck sees not a “nigger,” not a Black man, but a man. He plays a mean trick on Jim when they are well into their travels and it makes Huck “feel so mean I could almost kissed his foot to get him to take it back.”

Huck expresses his transformative experience, his moral awakening, after a series of struggles with his conscience: “It was fifteen minutes before I could work myself up to go and humble myself to a nigger – but I done it, and I warn’t ever sorry for it afterwards, neither. I didn’t do him no more mean tricks, and I wouldn’t done that one if I’d knowed it would make him feel that way.” No, the ugly term is not dropped but the attitude has been completely changed. He feels guilty and ashamed for hurting the feelings of a man he has come to like and respect. He sees Jim, for the first time, as someone with feelings and dignity – a fellow human being like himself. It is a dramatic moment in the novel, a pivotal moment that demonstrates the capacity for hatred and racism, learned from earliest childhood and deeply embedded in society, to be overcome and surpassed. It is a moment of lucidity that illuminates the novel and expresses a truth about the possibility of human nature to change and adapt.

One of the great strengths of literature is the creation of character. Huck enters our consciousness as a real person, someone you feel you know, however different from our life and our experience. That’s the point of literature –for the reader to see the world from someone else’s perspective, an insight into a different world that has the potential to transform us.

That is the core of this novel, its meaning and its greatness. Twain achieves that outstanding outcome by making the character of Huck believable. The character of Huckleberry Finn jumps off the page: the vocabulary is the vocabulary of the South of that era, the behavior is that of a youth who is searching for something he has yet to discover and an adventure that has many twists and turns that keep the reader entertained and engaged.

The novel ends on a relatively happy note in the sense that Jim does win his freedom, but Twain was wise enough to limit his ambition. The society is not changed but one boy has been changed. The magic of Twain is that the impossible is shown to be possible. If one person is subject to radical change and a Black man, a slave, in antebellum America, is respected and humanized, then it is possible for anyone to do the same.

The magic of Twain is that the impossible is shown to be possible. If one person is subject to radical change and a Black man, a slave, in antebellum America, is respected and humanized, then it is possible for anyone to do the same.

The novel takes place in various locations as Huck and Jim travel the Mississippi River to the free states. The journey on the river is also Huck’s moral journey from ignorance to enlightenment, from darkness to light, from prejudice to compassion. The journey takes him to the center of himself, a journey of self-discovery. Huck discovers much about human nature, and about himself. He may be very young – his age is not mentioned – but he learns from his experience.

Mark Twain was, in a sense, Huckleberry Finn. He was raised in Hannibal, Missouri, and shared the same prejudices as the people of his hometown. In 1860, a river captain told him about a Jew who saved a slave girl from death, and that incident may well have been responsible for his examining his own prejudices because Twain held positive views on Jews as well as Blacks. He called Jews “the world’s intellectual aristocracy” and, in 1909, his daughter, Clara, was engaged to a Russian-Jewish pianist. He called his essay “Concerning the Jews” “my gem of the ocean.” In the essay, he portrays the Jews most favorably: “He [the Jew] has made a marvellous fight in the world, in all the ages; and he has done it with his hands tied behind him…All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?”

So, Huck’s journey was Twain’s journey, but it extended beyond humanizing the Blacks to the Jews as well. Mark Twain was a most admirable man who used his great talent to expose the corrosive force of hatred and to demonstrate, in the most moving literature, the possibility for the individual to see beyond petty and dangerous small-mindedness, to summon conscience and generosity of spirit. Twain rose above the base and the negative and inspired others. He set an example in his own life and in his writing.

Mark Twain was a most admirable man who used his great talent to expose the corrosive force of hatred and to demonstrate, in the most moving literature, the possibility for the individual to see beyond petty and dangerous small-mindedness, to summon conscience and generosity of spirit.

Many years later, Nelson Mandela succinctly expressed the same idea of hope and possibility: “No one is born hating another person because of the colour of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.” In these dark times, it is important to remember Mark Twain and his creation, Huck Finn, and the possibilities they represent.

Dr. Paul Socken is Distinguished Professor Emeritus and founder of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Waterloo.