(JTA) — Germany’s pivotal national election takes place on Sunday, and one thing is sure: After 16 years in office, Chancellor Angela Merkel will not be at the helm any more.

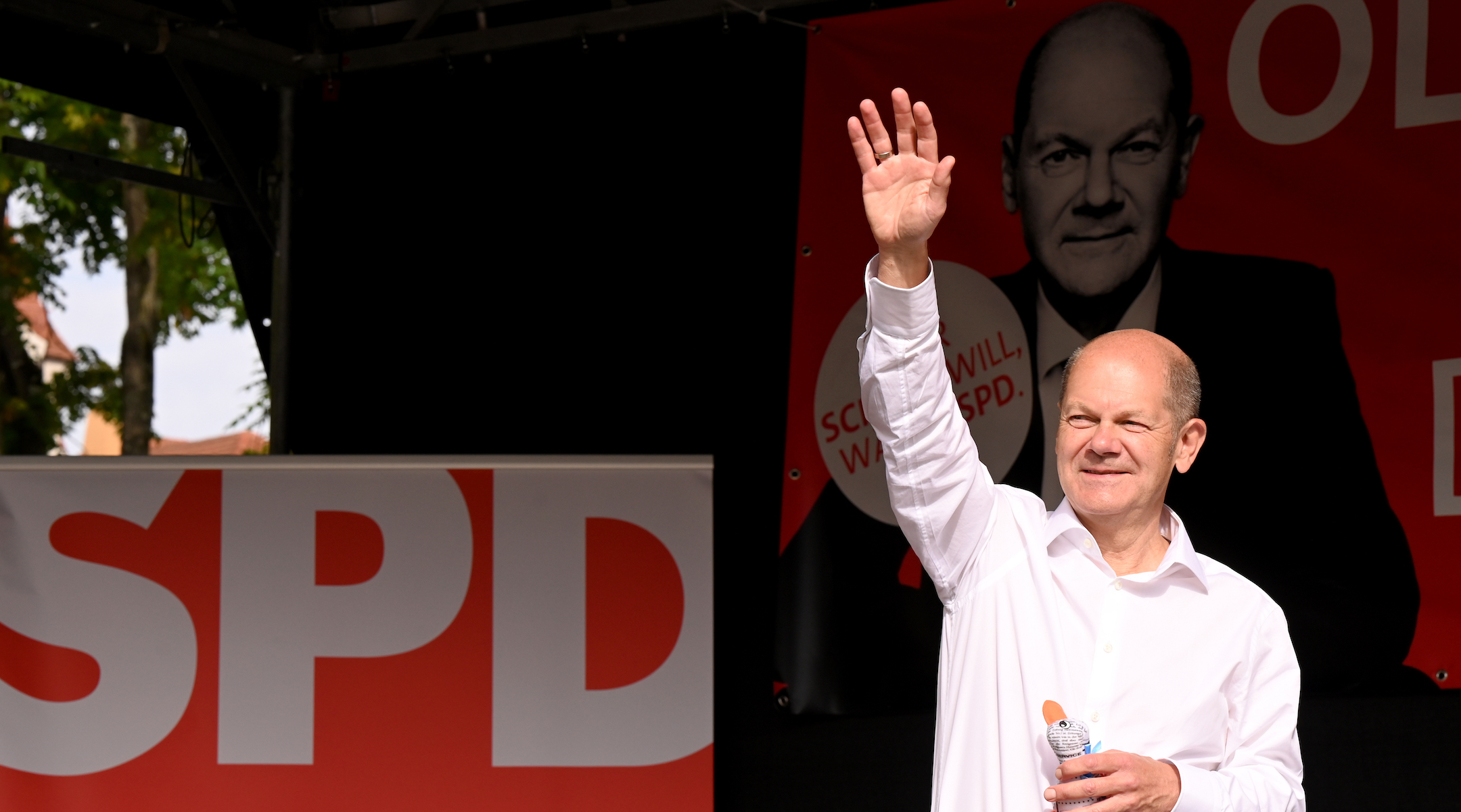

Who comes next? Pundits predict a new three-way coalition of center-left and moderate parties — most likely the Social Democrats, led by current Vice Chancellor Olaf Sholz; the left-leaning Greens, led by Annalena Baerbock; and the center-right Free Democratic Party, led by Christian Lindner.

Alternatively, Merkel’s party — the center-right Christian Democratic Union, or CDU, now headed by Armin Laschet — could be a second or third partner in a coalition.

Jews make up a tiny minority of the population — less than 200,000 in a country of 83 million — and they don’t vote as one.

“The Jewish vote in Germany is not big and not very important,” said Meron Mendel, director of the Frankfurt-based Anne Frank Educational Center. “Almost all of them are migrants from the former Soviet Union [and] their biggest concerns are not especially ‘Jewish’ but much more their situation [as newcomers] in Germany,” said Mendel, who came to Germany from Israel in 2001.

Though the Jewish vote is not courted in Germany the way it is in the United States, politicians do take note of particular issues of concern to Jews, in part out of a duty to ensure that the Holocaust not be forgotten.

“There is no data on what Jewish voters are interested in as a group, no survey,” said Dalia Grinfeld, a Berlin-based assistant director of European affairs for the Anti-Defamation League. “Jews are part of overall society and… they vote on different issues,” from climate change to health policy, from the economy to refugees, said Grinfeld, who was born in Stuttgart.

Furthermore, Jewish leaders, religious or political, generally don’t endorse parties. But observers are paying close attention to how the main democratic parties shake out on the big Jewish issues: antisemitism and its various sources, and Israel and other foreign policy.

With that in mind, in August the German Jewish ValuesInitiative — a non-partisan NGO that provides input for political decision makers and voters — sent a list of platform questions to all the parties in the Bundestag, or parliament, except for the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD.

Following suit, the Die Welt newspaper approached the heads of each party, drawing on the ValuesInitiative questions. They included the AfD, but its representative did not respond.

In their answers, the mainstream parties were barely distinguishable to the naked eye. Virtually all expressed support for Israel and the security of Jewish life in Germany, condemned antisemitism and came out in favor of reestablishing the nuclear disarmament agreement with Iran, as long as the country fulfills its obligations. Most want tougher controls on foreign funding of mosques in Germany. When it comes to standing up for Israel in the U.N., most said they would make decisions based on whether resolutions were fair and evenhanded.

Laschet said we will “clearly name and condemn attacks against Israel,” while Lindner wants Germany to “clearly distance itself from unilateral, primarily politically motivated initiatives and alliances of anti-Israeli member states” in United Nations bodies. Green candidate Annalena Baerbock called out the number of U.N. resolutions dealing with Israel as “absurd compared to resolutions against other states.”

“What [the parties] write is fine and good,” commented Elio Adler, founder and head of the ValuesInitiative, “but what counts is what they actually do.”

Christian Democratic Union party chairman Armin Laschet gestures during a press conference in Berlin, Sept. 20, 2021. (Clemens Bilan/Pool/Getty Images)

And what they do is influenced by what they think voters want. That could spell trouble for the special relationship between Germany and Israel, said Charlotte Knobloch, vice president of the European Jewish Congress and the World Jewish Congress.

“The slide from a mostly neutral stance toward more openly hostile views of Israel among the German public has become more and more evident,” said Knobloch, who survived the Holocaust in hiding and became a leader of the post-war Munich Jewish community.

She fears that the gap between politicians and the electorate “will only grow wider following Sept. 26.”

Some left-wing politicians avoid tackling anti-Israel movements and antisemitism in their midst, and far right politicians wrongly claim to be “a pro-Israel force and bulwark of Jewish life,” Knobloch argued. “We German Jews find ourselves between a rock and a hard place in this.”

Merkel disagreed with former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on some issues, including increased settlement construction, which she argued endangers her favored two-state solution. But she did not let those get in the way of a fruitful relationship with Israel.

“Anti-Zionism is on the rise in all political parties,” Jewish German columnist Michael Wuliger told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in an email. “Angela Merkel is probably the last leading German politician whose commitment to Israel was a matter of the heart.”

Antisemitism at home is a top issue. A 2018 European Union survey showed that 74.8% of Jewish respondents in Germany felt their government was not doing enough to combat the problem. One year later, a right-wing extremist tried to shoot his way into the Halle synagogue on Yom Kippur 2019, murdering two people on the street.

In 2020, the federal government pledged an extra $26 million to cover security costs for Jewish communities.

Baerbock told Die Welt her party wants to “promote Jewish life in its diversity in Germany and make it visible, in schools, in the breadth of society.” She urged “a paradigm shift” in dealing with threats to democratic values, and toward dismantling right-wing extremist networks. All Germans should “resolutely counter antisemitism and the spread of antisemitic conspiracy narratives,” she said.

In his answers, Sholz stressed the importance of funding civil society organizations that fight right-wing extremism and anti-Semitism. He said immigrants to Germany — including children — must have access to integration and language courses “from day one,” to stem the radicalization of young Muslims that many see as a key problem in Germany and other European nations. The SPD also plans to close extremist Islamist mosques and counter online hate propaganda.

While Adler’s ValuesIniative “will not express ourselves about individual parties; the only thing we have done is taken a clear position on the AfD.”

AfD party leaders have been accused of belittling the Holocaust, and recently have found favor with coronavirus deniers. In 2017, Bjoern Hoecke, AfD leader in the former East German state of Thuringia, criticized the Holocaust memorial in Berlin, telling a group of young party supporters that “Germans are the only people in the world who plant a monument of shame in the heart of the capital.” And in 2018, former AfD party head Alexander Gauland (now a representative in the Bundestag) said “Hitler and the Nazis are just birdshit in more than 1,000 years of successful German history.”

And now, “With the Covid pandemic, [the AfD] has unfortunately found a new topic after the refugee crisis,” said Josef Schuster, head of the Central Council, in an email to JTA. It “has ingratiated itself with the corona deniers and vaccination opponents in order to fish for votes there.” Schuster has recently rung alarm bells about Germans protesting coronavirus public safety measures who compare themselves to Anne Frank, or to other persecuted Jews by wearing yellow stars forced on them by Nazi Germany.

On Sept. 9, 60 Jewish groups joined a public appeal led by the Central Council of Jews in Germany, calling on citizens to “vote for a clearly democratic party and help kick the AfD out of the Bundestag.” Others signing on included the World Jewish Congress and European Jewish Congress, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, the Berlin office of the American Jewish Committee, Germany’s orthodox and liberal rabbinical conferences and rabbinical schools, Jewish student unions and a broad range of religious, political and educational groups.

That same day, the Anne Frank Educational Center issued a similar plea, reminding voters that if the AfD wins a second term in the Bundestag, it becomes eligible for tens of millions in taxpayer euros for its educational foundation.

It would be worse than ironic, said Mendel, director of the Anne Frank center, “when we are trying to educate for tolerance, democracy and diversity, and then the government would give millions of euros for a foundation that is trying to do exactly the opposite.”

Polls suggest the AfD is likely to lose votes this time around. But a party only needs 5% of the vote to secure a seat in the Bundestag. In the last federal election, they won 12.6%.

“Of course Jewish citizens are… interested in themes related to Jewish life,” said Adler. But they are also “normal citizens who also have other questions to which the parties must find answers.

“We are not only an indicator of the state of democracy, we are also a starting point for solutions.”