Shown here is an invitation to transportation and engineering forces in the British Army in Persia and Iraq for the “[Jewish] Officers and Other Ranks of No. 1. Pal. Docks & L. of C. Checking Coy.R.E. Paiforce” in Baghdad. The invitation is for “a party to be held on the occasion of the first anniversary of the joy and the feast of Chanukah on Tuesday, December 28, 1943 at 8:30 p.m.”

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 0 });

“L. of C.” (“Lines of Communication”) suggest temporary officers in the British Army Service Corps, and “R.E.” (the Corps of Royal Engineers commonly known as the “Sappers”) is a corps of the British Army that provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces.

“Paiforce” was the Persia and Iraq British Army Command established in Baghdad toward the end of World War II whose principal responsibilities were: (1) protecting the oilfields and oil installations in Iran and Iraq from land and air attack; and (2) ensuring the safety of supply transports from Persian Gulf ports through Iraq and Persia to the Soviet Union.

Much as the Maccabees of old attacked Greek supply trains en route to Jerusalem, the Jews of Paiforce ambushed German supply columns advancing to the Russian front, with many receiving high awards from the Russian government for their exceptional efforts.

This Baghdad Chanukah party was particularly poignant and emotional, coming as it did only two years after the Farhud – known as “the Kristallnacht of Iraqi Jewry” – when Iraqi police joined attacks upon the Jewish population and burned Jewish shops and destroyed synagogues.

The greatest pogrom in Iraqi history, the Farhud (Arabic for “violent dispossession”) was carried out against the Jews of Baghdad on Shavuot, June 1-2, 1941, during which at least 180 Jews were murdered (the Babylonian Heritage Museum in Israel states that an additional 600 unidentified victims were buried in a mass grave); over 1,000 were injured; and much Jewish property was destroyed, including over 900 Jewish homes.

The League of Nations had granted jurisdiction over Iraq to Britain after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Before the Nazis started intervening in Iraqi affairs, some 150,000 Iraqi Jews were intimately involved in their country’s social, political, and economic life, playing leading roles in farming, banking, commerce, and government. The Iraqi government promoted and supported Jewish identity, and even Zionism was tolerated until Nazi influence began to assert itself in internal Iraqi affairs in the 1930s.

Due to that influence, the government imposed restrictions on Jews, forbidding the teaching of Hebrew, levying additional licensing fees on various permits, and dismissing many Jews from their government employment. By the eve of the Farhud, Nazi propaganda had become endemic throughout Iraq, and Nazi supporters – including particularly Haj Amin Husseini, the notorious Grand Mufti of Jerusalem who had escaped the British by fleeing to Iraq from Eretz Yisrael – incited the population against the Jews.

There is considerable support for the proposition that the influence of German anti-Semitism on the Iraqi people was the primary cause of the Farhud uprising. Jews, who at the time comprised about one-third the population of Baghdad, had been living with their Iraqi neighbors in peaceful coexistence for thousands of years, enjoying relative peace and security; there had never before been a broad pogrom of this nature in Iraq; and, as noted above, Jews had historically played a significant role in Iraqi society. In a sad, but familiar, historical theme, most of these Jews saw themselves as members of Iraqi society first and Jews second.

In April 1940, nationalist Rashid Ali al-Keilan led the “Golden Square” – a group of pro-Nazi Iraqi officers – in a successful and popular coup, which overthrew Abdul Ilah, whom the British had installed as their governing regent in Iraq. Ali, a vehement anti-Semite and a fervent supporter of the Nazi regime, immediately began to challenge British hegemony, in response to which the British transferred many troops from India to Iraq to assert their authority.

On May 25, Hitler issued “Order 30,” pursuant to which he declared: “The Arab Freedom Movement in the Middle East is our natural ally against England. In this connection special importance is attached to the liberation of Iraq…. I have therefore decided to move forward in the Middle East by supporting Iraq.” Notwithstanding Germany’s assistance to Ali’s government, including providing air support and arms to Iraqi forces, Britain ultimately prevailed.

The Farhud rioting took place amidst the political vacuum that followed Ali’s defeat. Baghdad citizens who supported Ali found a convenient scapegoat for their loss: Iraqi Jews, whom they falsely alleged had collaborated and plotted with the British, arguing, among other things, that they had used radios to signal the British Royal Air Force.

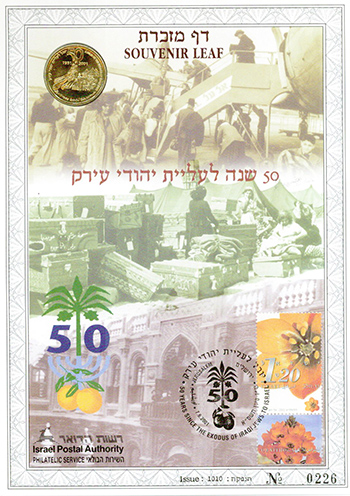

(Many scholars characterize the Farhud as “the beginning of the end of the Jewish community of Iraq,” which traces its history back to 586 BCE, and credit it with causing the mass migration of Jews out of Iraq, many going to Eretz Yisrael. Many Jews returned after World War II, only to leave the country a few years later as part of the mass 1951-52 Iraqi Jewish migration and, within a few years, only about 6,000 Jews remained in Iraq.)

Civil order was restored after two days of sustained violence when British troops imposed a curfew and shot violators on sight. Within a week, the British had ousted Ali’s government and reestablished the lawful Iraqi government. Investigations later showed that the two-day delay – which was responsible for great losses of Jewish life and property – was due to a unilateral decision by Kinahan Cornwallis, the British Ambassador to Iraq, not to carry out orders issued by the British Foreign Office, even going so far as to prohibit British entry into Baghdad until the pogrom had run its course.

* * * * *

Being away from family for the Jewish holidays is always dispiriting, but it is surely most difficult for American servicemen serving their country in war zones and hostile areas overseas. Besides experiencing the heartache of being away from their families, Jewish servicemen often face monumental obstacles in observing their holiday rites and traditions. Such difficulties include lack of access to necessary ritual items, such as matzah during Pesach and a menorah during Chanukah; the imperatives of their military duties; hostility from host countries toward Judaism; and, in some instances, even interference from their own anti-Semitic senior officers.

Although one would expect an American Jewish soldier serving in Iraq to encounter all four of these problems, they were barely an issue in 2005. What follows is the miraculous and astonishing story of the Chanukah celebration that took place that year in what was arguably the most unlikely place for such a celebration: Saddam Hussein’s Republican Presidential Palace.

In October 2005, several American Jewish servicemen came up with the idea of holding organized Chanukah celebrations in Iraq. Their party planning began with contacting several organizations for support and, with the encouragement of their commander, Colonel Nelson Mellitz, requests were made through the American Embassy in Iraq, the Chaplain’s Services, and Jewish War Veterans USA. The word successfully spread to the point where Chanukah paraphernalia (menorahs, dreidels, etc.) inundated Mellitz’s office.

The effort was not entirely smooth, as some officers created unnecessary obstacles to the proposed parties – some say due to anti-Semitism – but, at the end of the day, the issues were resolved at the highest levels, including the involvement of the American ambassador to Iraq. The planning proceeded apace, and the decision was made to hold the festivities at Saddam Hussein’s former palace. Over 150,000 e-mail invitations announced: “Giant menorah lighting. Kosher potato pancakes. Come spin the dreidel. Everybody’s welcome. Dec. 25.”

One remaining problem, however, was how Jewish servicemen on assignment could get away to attend the party. Through an interdenominational agreement, Christian servicemen traditionally substituted for their fellow Jews on Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Passover, while Jews worked for their Christian comrades-in-arms on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter, but that longstanding arrangement made no provision for Chanukah. However, in a lovely exhibition of thoughtfulness and consideration, non-Jewish personnel insisted upon remaining on duty so their Jewish mates could attend the party – which they did in droves.

This great act of kindness was particularly extraordinary because the Chanukah celebration was held on Christmas that year, and the non-Jews – who appreciated the incredible symbolism of lighting a menorah at Saddam’s palace while the former despot was still alive and imprisoned across the street – willingly forfeited their own holiday celebration. (Saddam Hussein was hanged on December 30, 2006 after being convicted of committing crimes against humanity.)

The party featured music and dancing; latkes and applesauce, chocolates, eggnog, and other delectables; dreidel-spinning; and speeches from dignitaries including, in an important and conspicuous statement of American support, the American Ambassador to Iraq, Zalmay Khalilzad.

The high point of the celebration was the public lighting of an enormous menorah that had been designed by L.T. Laurie and built by KBR, a government military engineering and construction contractor, and by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which reportedly had no clue what a menorah was until they were charged with building one. A photograph of the 12-foot menorah sitting in Saddam’s throne room appeared on the front page of Stars and Stripes.

The imagery is stark, and the confluence of themes between “now and then” is obvious: Saddam and the Hellenist Syrian king, Antiochus IV, both ruthless and inhumane tyrants; the inherent ungodliness of both the Iraqi and Syrian regimes, contrasted against the virtuousness of American forces and the Maccabees; the incredible American victory in Iraq and the Jewish military victory in Eretz Yisrael (which is actually the true essence of the Chanukah miracle); the revival of Baghdad as a capital city in a newly free Iraq and the revival of Jerusalem as the Jewish capital city; the restrictions on religious practice by the Syrians and Iraqis vs. the values of American pluralism and the freedom of Jewish servicemen to practice the faith of their forefathers even in the proverbial heart of the lion’s den; the ultimate triumph of good over evil “bayamin hahem bazeman hazeh – in those days, at this time”; and, last but not least, the inspiring and momentous symbolism of banishing darkness with the lighting of a menorah in both Saddam’s former seat of power and in the Beit HaMikdash, representing both the overthrow of tyranny and the eternity of the Jewish people.

As one writer so beautifully put it, “This Chanukah in Baghdad, in a large and lavish building, the gentle glow of a Chanukah lamp shimmered throughout a cavernous room. One of the objects caught in its radiance is a gilded chair that used to serve as the tyrant’s throne, and the palace in which it sits used to be the capital building of his reign of terror. Today, the chair is empty, and the palace houses the apparatus of Iraqi reconstruction.”

Wishing all a Chag Urim Sameach.

‘);

_avp.push({ tagid: article_top_ad_tagid, alias: ‘/’, type: ‘banner’, zid: ThisAdID, pid: 16, onscroll: 10 });