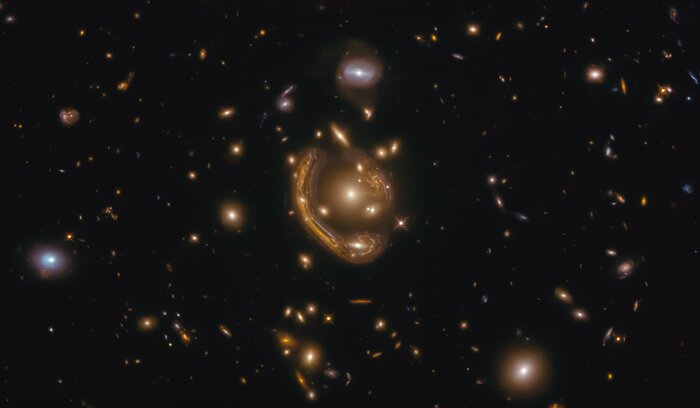

An image ESA/Hubble published in 2020, showed the largest and one of the most complete Einstein rings ever discovered, dubbed the “Molten Ring” by the Hubble observation’s Principal Investigator, which alludes to its appearance and host constellation in the southern hemisphere constellation of Fornax (The Furnace).

Einstein first proposed the existence of this object in his general theory of relativity, and its unusual shape can be explained by a process called gravitational lensing, which causes light shining from a great distance to be bent and pulled by the gravity of an object between the source and observer.

In this scenario, the gravity of the galaxy cluster in front of it has warped the light from the background galaxy into the curve we observe. Due to the near-perfect alignment of the background galaxy with the galaxy cluster’s center, visible in the center of this image, the image of the background galaxy has been twisted and magnified into an almost perfect ring. Additional distortions are imminent due to the gravity of the cluster’s galaxies.

A group of European astronomers has now studied the Einstein ring in depth using a multi-wavelength dataset that includes data from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and this featured image.

“In order to derive the physical properties of the lensed galaxy a lensing model is needed. Such a model could only be obtained with the Hubble imaging,” explained the lead investigator Anastasio Díaz-Sánchez of the Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena in Spain. “In particular, Hubble helped us to identify the four counter images and the stellar clumps of the lensed galaxy, for which the Picture of the Week image was used.”

The scientists determined the amplification factor using this lensing model, which is a valuable effect of gravitational lensing. This enabled the team to investigate the lensed galaxy’s intrinsic physical features. The determination of the galaxy’s distance is particularly interesting, as it indicates that the galaxy’s light has traveled around 9.4 billion light-years.

“The detection of molecular gas, from which new stars are born, enabled us to calculate the precise redshift, which reassures us that we are indeed looking at a very distant galaxy,” said Nikolaus Sulzenauer, a PhD student at Germany’s Max Plank Institute for Radio Astronomy and a member of the investigation team.

Additionally, the team assessed the galaxy’s magnification factor to be 20, equating Hubble’s seeing power to that of a 48-metre telescope. This is larger than the exceedingly huge telescopes currently proposed.

“The Hubble images vividly depict the spiral arms and the bulge at the galaxy’s center. This will contribute to our understanding of star formation in distant galaxies via upcoming surveys,” team member Susana Iglesias-Groth of Spain’s Institute of Astrophysics noted.

“The Hubble photos vividly show the spiral arms and the galaxy’s center bulge. This will aid in our understanding of star formation in distant galaxies through planned surveys,” stated team member Susana Iglesias-Groth of Spain’s Institute of Astrophysics.