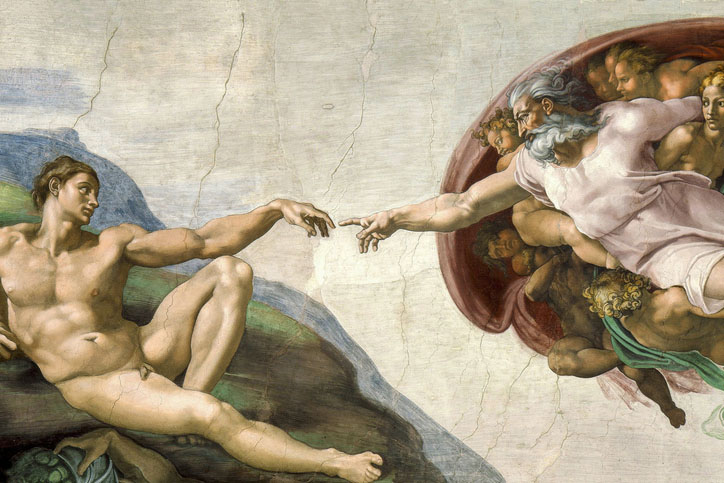

The rationale of the brief biblical creation narrative we read

in Genesis may be to teach us that its goal

reached — on its seventh day, which satisfied humanity’s great need

to rest — not just all people’s bodies but their soul.

God’s was the spirit that created all the universe,

whose climax was the Sabbath day, and not humanity,

a day on which all Jews who are devout rehearse

a weekly play God premiered. Protected from profanity

by performance of this play one day each week,

Jews justify creation of the world by resting

like God, the world’s creator, when we seek

to imitate Him, like Him on his day in holiness investing.

None of the rationales of Genesis’s description

explain scientifically how by God the universe was formed.

Chief of the rationales was the sabbatical prescription

enabling all our motions to be once a week reformed,

a rationale for Sabbath which I presume

God does need, Scriptwriter of the universe,

providing it to Jewish people to prevent a doom

which, God forbid, would make the world’s prognosis worse,

implying that the way the creation story’s leitmotif

is not literally true reflects how Moses, God’s greatest Veep,

tells us in Deuteronomy 6: 5 to love His Chief,

a metaphor about a God who though He rests on Sabbath, does not sleep.

In “The Vatican Observatory Looks to the Heavens: It’s run by a Michigan-born Jesuit—and a meteorite expert—known as the Pope’s Astronomer,” New Yorker, 7/28/25, by Rebecca Mead writes:

….Castel Gandolfo is also home to one of the Holy See’s more unexpected institutions: the Vatican Observatory, which since its founding, in 1891, has been dedicated to the scientific study of the heavens.

Guy Consolmagno, the director of the observatory, first came to Castel Gandolfo as a newly minted Jesuit brother, in 1993…

…The secular world, meanwhile, has often attacked the Church as a peddler of absurd fantasies. In recent decades, writers grouped under the rubric the New Atheists—among them Christopher Hitchens, the swingeing author of “God Is Not Great,” and Richard Dawkins, who wrote the intemperate book “The God Delusion”—have decried organized religions for their damaging superstitions and mystifications, and have championed an explanatory rationalism in their stead. In “God Is Not Great,” Hitchens, who died in 2011, wrote, “If you will devote a little time to studying the staggering photographs taken by the Hubble telescope, you will be scrutinizing things that are far more awesome and mysterious and beautiful—and more chaotic and overwhelming and forbidding—than any creation or ‘end of days’ story.” The New Atheists were revisiting debates from the nineteenth century, when influential critics, among them Andrew Dickson White, the first president of Cornell University, sought to reëxamine established religions in the light of recent scientific discoveries. In “A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom,” published in 1896, White wrote that “dogmatic theology”—rigid interpretations of religious doctrine—inherently clashed with scientific findings, which were constantly evolving because of new thinking and technologies.

According to Consolmagno, the arguments put forward by the New Atheists and their ilk invoke what you might call a straw God. “When I say, ‘I believe in God,’ it means that I believe in one God, which means there are a whole lot of versions of God out there that I don’t believe in,” he told me. “An atheist, in order to be an atheist, has to have a really clear idea of who the God is they don’t believe in. More often than not, they are right—the God they don’t believe in I don’t believe in, either.” Consolmagno’s Catholic faith does not require that he believe the world was literally created in seven days, and he pities would-be astrophysicists who grew up in fundamentalist Christian traditions. Once, while visiting Oral Roberts University, in Tulsa, he stumbled across a way of expressing his perspective on the Book of Genesis: “I pointed out that the seven days of creation tell us not about creation but about God,” he recalled. “If you put that emphasis on it, I think you get closer to what the author of Genesis really wanted to do, which was to talk about God. What’s the goal of Genesis? It’s the seventh day, the Sabbath. And what’s the Sabbath? It’s when we start thinking about the universe, and the creator, rather than just worrying about feeding ourselves, and that’s what makes us people, rather than animals. God calls us to be astronomers. Not only is it clever—it might even be true.”

The last verse was inspired by “The Mitzvah to Love God: Shadal’s Polemic against the Philosophical Interpretation,” Marty Lockshin’s discussion of the explanation, that offered by Shadal (Samuel David Luzzatto; 1800-1865) in his commentary to Deuteronomy 6:5, provides a unique window into problems encountered when trying to read this mitzvah through a medieval philosophical lens.

….Philosophically inclined rabbis, such as Maimonides, attempted to understand the mitzvah to love God in Aristotelian terms, imagining God as a non-anthropomorphic abstract being. Shadal argues that this elitist approach twists both Torah and philosophy, and in its place, he offers a moralistic approach that can be achieved by all.

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at [email protected].