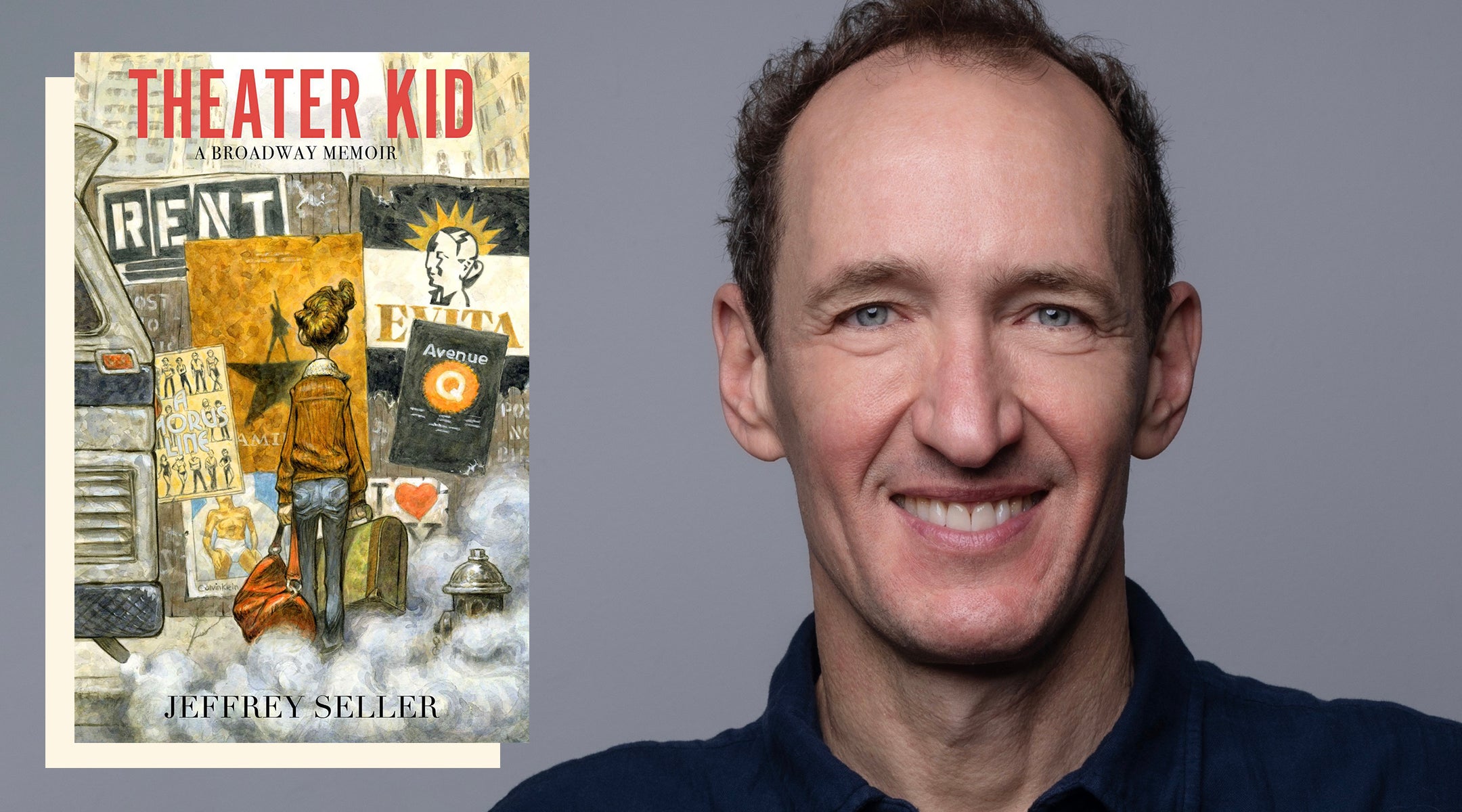

It’s possible that you’ve never heard of theater producer Jeffrey Seller. But even someone with a passing knowledge of Broadway musicals will likely know the award-winning shows that he’s produced, including “Rent,” “Hamilton” and “Avenue Q.”

Over his 40-year career, Seller, 60, who was raised in a Reform Jewish family in suburban Detroit, has earned a whopping 22 Tony awards — including four for Best Musical — and is the only producer behind two Pulitzer Prize-winning musicals.

Now, with his new memoir, “Theater Kid,” Seller takes readers behind the scenes of his Broadway success. And while there are juicy details about the rush, and mishaps, that shot his first Broadway show, “Rent,” to legendary status — like the time the musical’s sign was incorrectly rendered, creating the iconic transparent logo — Seller’s story isn’t all glamour. Seller takes us all the way back to his humble beginnings, taking great pains describing his experience growing up Jewish and adopted, navigating childhood poverty, and coming into his identity as a gay man.

“This was a coming-out story,” Seller told the New York Jewish Week. “This was a story about overcoming shame. And it’s a story of Genesis.”

Though Seller has spent decades working with playwrights, “Theater Kid” is his first foray into authorship. Many of the anecdotes in the book were jotted down in his 20s and stuffed in a drawer for decades, he said, until he worked up the courage to share them.

“Theater Kid” took Seller six years to aggregate, organize and edit. During the process, Seller hoped to reflect upon and understand how he achieved his dreams: “I wanted to write down how the poor, adopted Jewish gay kid got from ‘Cardboard Village’ in Oak Park, Michigan to Broadway, because I wanted to know for myself, ‘How did you do it?’”

“Theater Kid” follows Seller from his childhood in the Great Lakes State to the Great White Way, detailing how he first discovered theater — performing in a Purim play at Temple Israel in West Bloomfield, Michigan — as well as his struggles at home. Seller describes how his family faced financial instability after his father suffered brain damage from a motorcycle accident. While his dad occasionally worked as a process server, the family relied on his mother’s drugstore wages and support from Jewish Family Services.

Seller recalls a strong sense of class consciousness growing up among wealthier classmates in suburban Detroit. In one of the book’s saddest moments, Seller describes his Hebrew school teacher comparing the poverty in his working-class neighborhood to the Warsaw Ghetto.

Seller said he was especially grateful for the Temple Israel rabbis, who allowed him and his siblings to attend Hebrew school for free — and his parents’ insistence on taking him, no matter their struggles.

“One of the things that I found amazing, looking back, is how my Jewish parents, who were falling apart in so many ways, who were at one point on welfare, who were dealing with chaos, trauma and poverty, still managed to get me to Temple Israel’s religious school every Sunday morning,” he said.

His love of theater was born at the Reform synagogue, where Seller discovered that he wasn’t just captivated by being onstage — he was enamored by how the entire machine of theater worked.

“The Purim play opened up an entire world of creativity and wonder and storytelling and music that was better than anything going on in my everyday life, and I realized this gives me purpose,” he said. “This gives me the opportunity to make something, and this is where I want to belong.”

After four years at the University of Michigan — where he dated Jewish composer Andrew Lippa — Seller set his sights on something bigger: New York City.

Seller arrived in New York City in 1986 with dreams of becoming a theater director. He took odd jobs like answering phones at production companies to get by, but it was an unexpected side gig at Temple Rodeph Sholom on the Upper West Side that became a turning point. Seller convinced the congregation to fund “A Pound of Feathers,” a musical based on his college friend’s play, “Shtetl Tales.” He hired a composer and writer, and directed it himself.

The experience taught Seller something crucial: While he loved all aspects of theater, his true talents lay in producing. As he juggled odd jobs around the city, he also set his sights on a personal goal, too: He no longer wanted to feel like an outsider in the Big Apple.

By then, it was the late 1980s, and Seller was still hustling and living in Park Slope, Brooklyn. One day, he impulsively laced up his sneakers and ran across the Brooklyn Bridge. “I just remember looking at the skyline and going, that’s going to be mine,” he recalled. “I’m going to do this. I am going to make it here. That is going to be my city.”

That rush of adrenaline turned into a kind of vow. It wasn’t just the skyline that moved him — it was what it represented: the possibility of becoming part of New York’s creative fabric. Seller didn’t yet have the titles or the clout, but what he did have was grit. In the years that followed, he worked every angle he could: answering phones for producers, reading unsolicited scripts, sitting in the back of rehearsal rooms, and learning the industry from the inside out. That bridge run didn’t launch his career — but it marked the moment he decided he’d stop waiting for permission to be part of Broadway.

It was that newly-ignited sense of purpose that led him to a young Jonathan Larson, the Jewish composer of “Boho Days,” which evolved into his semi-autobiographical musical “Tick, Tick… BOOM!” Seller became an early advocate for Larson’s raw but groundbreaking work, which culminated in “Rent,” the rock opera about young bohemians living through the AIDS crisis in New York City.

The show launched Seller — and posthumously, Larson, who died of an aortic dissection the morning of its off-Broadway preview — into Broadway stardom. Seller would replicate that success with “In the Heights,” “Hamilton,” and “Avenue Q,” each breaking boundaries in their own way.

Soon enough, Seller began to live the life he dreamed of when he first came to New York. These days, he resides in his dream neighborhood, the Upper West Side, with his two children. He’s an active member of Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, a progressive and pluralistic LGBTQ+ synagogue in Chelsea.

Despite his impressive Broadway record, Seller resists the idea that he holds the formula for a cultural juggernaut. The truth, he said, is more elusive — and more difficult to achieve.

“It’s the audience who decides,” he said. “All I can do is look back and try to hypothesize why something landed the way it did.”

“Theater Kid” also tackles the political power of musicals and how their impact doesn’t end when the curtain drops. He’s most proud, he said, when a show becomes not just a commercia hit but a cultural phenomenon that helps shape public policy.

With “Rent,” the impact was tangible. “In the years after it opened [in 1996], more young people were tested for HIV,” Seller said, adding that more testing helped pave the way for fewer new cases. The musical helped humanize the AIDS crisis and, as he put it, acted as “soft diplomacy” for LGBTQ+ rights.

Then came “Hamilton,” which Seller views as similarly transformative. It reignited interest in early American history, and the musical’s popularity possibly swayed then-Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew in 2016 to keep Alexander Hamilton on the $10 bill, in lieu of replacing him with Harriet Tubman.

“That’s an example of a work of musical theater that directly affects public policy,” he said.

That power surfaced again later that year, when Vice President-elect Mike Pence attended “Hamilton.” At curtain call, actor Brandon Victor Dixon read a letter Seller co-wrote with the show’s creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda, urging the incoming administration to protect the rights of all Americans.

“Sadly, everything we expressed worry about in that letter came true,” Seller said.

Still, Seller ends his memoir at that moment to underscore the capacity of theater to effect change. Ultimately, his message to his audiences and readers is a simple one: “Protest works,” he said. “So when you can be part of it with a musical — join in.”

Jewish stories matter, and so does your support.